Section 15.5 : Triple Integrals

Now that we know how to integrate over a two-dimensional region we need to move on to integrating over a three-dimensional region. We used a double integral to integrate over a two-dimensional region and so it shouldn’t be too surprising that we’ll use a triple integral to integrate over a three dimensional region. The notation for the general triple integrals is,

\[\iiint\limits_{E}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dV}}\]Let’s start simple by integrating over the box,

\[B = \left[ {a,b} \right] \times \left[ {c,d} \right] \times \left[ {r,s} \right]\]Note that when using this notation we list the \(x\)’s first, the \(y\)’s second and the \(z\)’s third.

The triple integral in this case is,

\[\iiint\limits_{B}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dV}} = \int_{{\,r}}^{{\,s}}{{\int_{{\,c}}^{{\,d}}{{\int_{{\,a}}^{{\,b}}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)dx}}\,dy}}\,dz}}\]Note that we integrated with respect to \(x\) first, then \(y\), and finally \(z\) here, but in fact there is no reason to the integrals in this order. There are 6 different possible orders to do the integral in and which order you do the integral in will depend upon the function and the order that you feel will be the easiest. We will get the same answer regardless of the order however.

Let’s do a quick example of this type of triple integral.

Just to make the point that order doesn’t matter let’s use a different order from that listed above. We’ll do the integral in the following order.

\[\begin{align*}\iiint\limits_{B}{{8xyz\,dV}} & = \int_{{\,1}}^{{\,2}}{{\int_{{\,2}}^{{\,3}}{{\int_{{\,0}}^{1}{{8xyz\,dz}}\,dx}}\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{{\,1}}^{{\,2}}{{\int_{{\,2}}^{{\,3}}{{\left. {4xy{z^2}} \right|_0^1\,dx}}\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{{\,1}}^{{\,2}}{{\int_{{\,2}}^{{\,3}}{{4xy\,dx}}\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{{\,1}}^{{\,2}}{{\left. {2{x^2}y} \right|_2^3\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{{\,1}}^{{\,2}}{{10y\,dy}} = 15\end{align*}\]Before moving on to more general regions let’s get a nice geometric interpretation about the triple integral out of the way so we can use it in some of the examples to follow.

Fact

The volume of the three-dimensional region \(E\) is given by the integral,

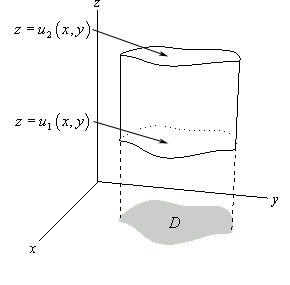

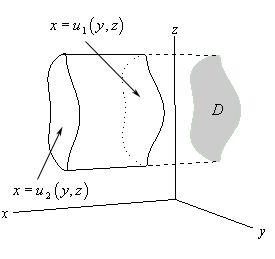

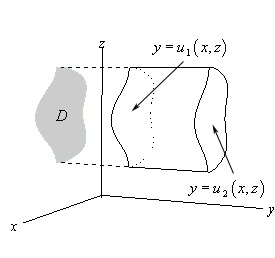

\[V = \iiint\limits_{E}{{\,dV}}\]Let’s now move on the more general three-dimensional regions. We have three different possibilities for a general region. Here is a sketch of the first possibility.

In this case we define the region \(E\) as follows,

\[E = \left\{ {\left( {x,y,z} \right)|\left( {x,y} \right) \in D,\,\,\,{u_1}\left( {x,y} \right) \le z \le {u_2}\left( {x,y} \right)} \right\}\]where \(\left( {x,y} \right) \in D\) is the notation that means that the point \(\left( {x,y} \right)\) lies in the region \(D\) from the \(xy\)-plane. In this case we will evaluate the triple integral as follows,

\[\iiint\limits_{E}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dV}} = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{{\,{u_1}\left( {x,y} \right)}}^{{\,{u_2}\left( {x,y} \right)}}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dz}}} \right]\,dA}}\]where the double integral can be evaluated in any of the methods that we saw in the previous couple of sections. In other words, we can integrate first with respect to \(x\), we can integrate first with respect to \(y\), or we can use polar coordinates as needed.

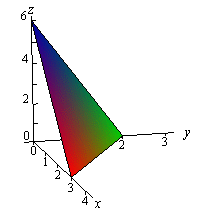

We should first define octant. Just as the two-dimensional coordinates system can be divided into four quadrants the three-dimensional coordinate system can be divided into eight octants. The first octant is the octant in which all three of the coordinates are positive.

Here is a sketch of the plane in the first octant.

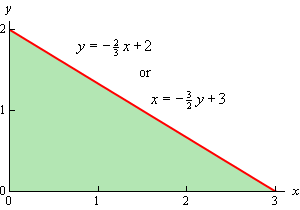

We now need to determine the region \(D\) in the \(xy\)-plane. We can get a visualization of the region by pretending to look straight down on the object from above. What we see will be the region \(D\) in the \(xy\)-plane. So \(D\) will be the triangle with vertices at \(\left( {0,0} \right)\), \(\left( {3,0} \right)\), and \(\left( {0,2} \right)\). Here is a sketch of \(D\).

Now we need the limits of integration. Since we are under the plane and in the first octant (so we’re above the plane \(z = 0\)) we have the following limits for \(z\).

\[0 \le z \le 6 - 2x - 3y\]We can integrate the double integral over \(D\) using either of the following two sets of inequalities.

\[\begin{matrix} \begin{aligned} & \,\,\,\,\,\,0\le x\le 3 \\ & 0\le y\le -\frac{2}{3}x+2 \\ \end{aligned} & \hspace{0.5in} & \begin{aligned} & 0\le x\le -\frac{3}{2}y+3 \\ & \,\,\,\,\,\,0\le y\le 2 \\ \end{aligned} \\ \end{matrix}\]Since neither really holds an advantage over the other we’ll use the first one. The integral is then,

\[\begin{align*}\iiint\limits_{E}{{2x\,dV}} &= \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{{\,0}}^{{6 - 2x - 3y}}{{2x\,dz}}} \right]\,dA}}\\ & = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left. {2xz} \right|_0^{6 - 2x - 3y}\,dA}}\\ & = \int_{{\,0}}^{{\,3}}{{\int_{0}^{{ - \frac{2}{3}x + 2}}{{2x\left( {6 - 2x - 3y} \right)\,dy}}\,dx}}\\ & = \int_{0}^{3}{{\left. {\left( {12xy - 4{x^2}y - 3x{y^2}} \right)} \right|_0^{ - \frac{2}{3}x + 2}\,dx}}\\ & = \int_{0}^{3}{{\frac{4}{3}{x^3} - 8{x^2} + 12x\,dx}}\\ & = \left. {\left( {\frac{1}{3}{x^4} - \frac{8}{3}{x^3} + 6{x^2}} \right)} \right|_0^3\\ & = 9\end{align*}\]Let’s now move onto the second possible three-dimensional region we may run into for triple integrals. Here is a sketch of this region.

For this possibility we define the region \(E\) as follows,

\[E = \left\{ {\left( {x,y,z} \right)|\left( {y,z} \right) \in D,\,\,\,{u_1}\left( {y,z} \right) \le x \le {u_2}\left( {y,z} \right)} \right\}\]So, the region \(D\) will be a region in the \(yz\)-plane. Here is how we will evaluate these integrals.

\[\iiint\limits_{E}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dV}} = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{{\,{u_1}\left( {y,z} \right)}}^{{\,{u_2}\left( {y,z} \right)}}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dx}}} \right]\,dA}}\]As with the first possibility we will have two options for doing the double integral in the \(yz\)-plane as well as the option of using polar coordinates if needed.

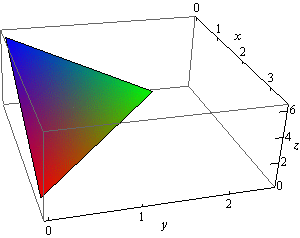

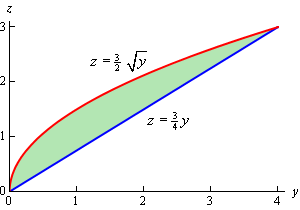

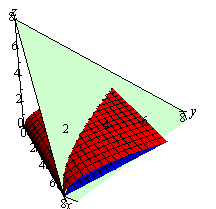

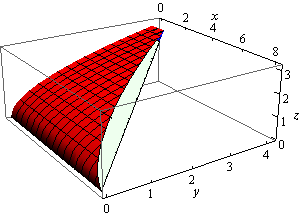

In this case we’ve been given \(D\) and so we won’t have to really work to find that. Here is a sketch of the region \(D\) as well as a quick sketch of the plane and the curves defining \(D\) projected out past the plane so we can get an idea of what the region we’re dealing with looks like.

Now, the graph of the region above is all okay, but it doesn’t really show us what the region is. So, here is a sketch of the region itself.

Here are the limits for each of the variables.

\[\begin{array}{c}0 \le y \le 4\\ \displaystyle \frac{3}{4}y \le z \le \frac{3}{2}\sqrt y \\ 0 \le x \le 8 - y - z\end{array}\]The volume is then,

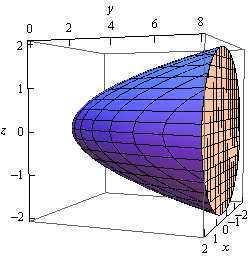

\[\begin{align*}V &= \iiint\limits_{E}{{\,dV}} = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{0}^{{8 - y - z}}{{\,dx}}} \right]\,dA}}\\ & = \int_{0}^{4}{{\int_{{{{3y}}/{4}\;}}^{{{{3\sqrt y }}/{2}\;}}{{8 - y - z\,dz}}\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{0}^{4}{{\left. {\left( {8z - yz - \frac{1}{2}{z^2}} \right)} \right|_{\frac{{3y}}{4}}^{\frac{{3\sqrt y }}{2}}\,dy}}\\ & = \int_{0}^{4}{{12{y^{\frac{1}{2}}} - \frac{{57}}{8}y - \frac{3}{2}{y^{\frac{3}{2}}} + \frac{{33}}{{32}}{y^2}\,dy}}\\ & = \left. {\left( {8{y^{\frac{3}{2}}} - \frac{{57}}{{16}}{y^2} - \frac{3}{5}{y^{\frac{5}{2}}} + \frac{{11}}{{32}}{y^3}} \right)} \right|_0^4 = \frac{{49}}{5}\end{align*}\]We now need to look at the third (and final) possible three-dimensional region we may run into for triple integrals. Here is a sketch of this region.

In this final case \(E\) is defined as,

\[E = \left\{ {\left( {x,y,z} \right)|\left( {x,z} \right) \in D,\,\,\,{u_1}\left( {x,z} \right) \le y \le {u_2}\left( {x,z} \right)} \right\}\]and here the region \(D\) will be a region in the \(xz\)-plane. Here is how we will evaluate these integrals.

\[\iiint\limits_{E}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dV}} = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{{\,{u_1}\left( {x,z} \right)}}^{{\,{u_2}\left( {x,z} \right)}}{{f\left( {x,y,z} \right)\,dy}}} \right]\,dA}}\]where we can use either of the two possible orders for integrating \(D\) in the \(xz\)-plane or we can use polar coordinates if needed.

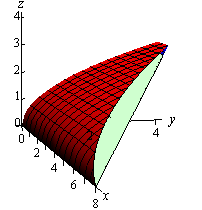

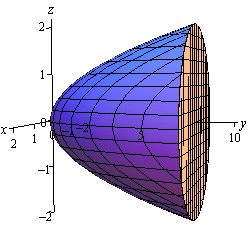

Here is a sketch of the solid \(E\).

The region \(D\) in the \(xz\)-plane can be found by “standing” in front of this solid and we can see that \(D\) will be a disk in the \(xz\)-plane. This disk will come from the front of the solid and we can determine the equation of the disk by setting the elliptic paraboloid and the plane equal.

\[2{x^2} + 2{z^2} = 8\hspace{0.25in} \Rightarrow \hspace{0.25in}{x^2} + {z^2} = 4\]This region, as well as the integrand, both seems to suggest that we should use something like polar coordinates. However, we are in the \(xz\)-plane and we’ve only seen polar coordinates in the \(xy\)-plane. This is not a problem. We can always “translate” them over to the \(xz\)-plane with the following definition.

\[x = r\cos \theta \hspace{0.25in}\hspace{0.25in}z = r\sin \theta \]Since the region doesn’t have \(y\)’s we will let \(z\) take the place of \(y\) in all the formulas. Note that these definitions also lead to the formula,

\[{x^2} + {z^2} = {r^2}\]With this in hand we can arrive at the limits of the variables that we’ll need for this integral.

\[\begin{array}{c}2{x^2} + 2{z^2} \le y \le 8\\ 0 \le r \le 2\\ 0 \le \theta \le 2\pi \end{array}\]The integral is then,

\[\begin{align*}\iiint\limits_{E}{{\sqrt {3{x^2} + 3{z^2}} \,dV}} & = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left[ {\int_{{2{x^2} + 2{z^2}}}^{{\,8}}{{\sqrt {3{x^2} + 3{z^2}} \,dy}}} \right]\,dA}}\\ & = \iint\limits_{D}{{\left. {\left( {y\sqrt {3{x^2} + 3{z^2}} } \right)} \right|_{2{x^2} + 2{z^2}}^8\,dA}}\\ & = \iint\limits_{D}{{\sqrt {3\left( {{x^2} + {z^2}} \right)} \left( {8 - \left( {2{x^2} + 2{z^2}} \right)} \right)\,dA}}\end{align*}\]Now, since we are going to do the double integral in polar coordinates let’s get everything converted over to polar coordinates. The integrand is,

\[\begin{align*}\sqrt {3\left( {{x^2} + {z^2}} \right)} \left( {8 - \left( {2{x^2} + 2{z^2}} \right)} \right) &= \sqrt {3{r^2}} \left( {8 - 2{r^2}} \right)\\ & = \sqrt 3 \,\,r\left( {8 - 2{r^2}} \right)\\ & = \sqrt 3 \left( {8r - 2{r^3}} \right)\end{align*}\]The integral is then,

\[\begin{align*}\iiint\limits_{E}{{\sqrt {3{x^2} + 3{z^2}} \,dV}} & = \iint\limits_{D}{{\sqrt 3 \,\,\left( {8r - 2{r^3}} \right)dA}}\\ & = \sqrt 3 \int_{{\,0}}^{{\,2\pi }}{{\int_{{\,0}}^{{\,2}}{{\left( {8r - 2{r^3}} \right)r\,dr}}\,d\theta }}\\ & = \sqrt 3 \int_{{\,0}}^{{\,2\pi }}{{\left. {\left( {\frac{8}{3}{r^3} - \frac{2}{5}{r^5}} \right)} \right|_0^2\,d\theta }}\\ & = \sqrt 3 \int_{{\,0}}^{{\,2\pi }}{{\frac{{128}}{{15}}\,d\theta }}\\ & = \frac{{256\sqrt 3 \,\pi }}{{15}}\end{align*}\]